Replication slots in Postgres keep track of how far consumers have read a replication stream. After a restart, consumers—either Postgres read replicas or external tools for change data capture (CDC), like Debezium—resume reading from the last confirmed log sequence number (LSN) of their replication slot. The slot prevents the database from disposing of required log segments, allowing safe resumption after downtime.

In this post, we are going to take a look at why Postgres replication slots don’t have one but two LSN-related attributes: restart_lsn and confirmed_flush_lsn.

Understanding the difference between the two is crucial for troubleshooting replication issues, optimizing WAL retention, and avoiding common pitfalls in production environments.

To examine the state of a replication slot, you can query the pg_replication_slots view.

It also shows the restart_lsn and confirmed_flush_lsn of each slot:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

SELECT

slot_name, plugin, restart_lsn, confirmed_flush_lsn

FROM

pg_replication_slots;

+----------------+---------------+-------------+---------------------+

| slot_name | plugin | restart_lsn | confirmed_flush_lsn |

|----------------+---------------+-------------+---------------------|

| logical_slot_4 | pgoutput | 0/1D4A478 | 0/1D52850 |

| demo_slot | test_decoding | 0/1DDC4D0 | 0/1DDC4D0 |

+----------------+---------------+-------------+---------------------+

So what’s the difference between the two? Shouldn’t a single LSN be enough for tracking the progress a consumer has made?

confirmed_flush_sn: Tracking Consumer Progress

In order to understand why Postgres manages these two LSN separately,

let’s take a look at what the Postgres docs have to say,

starting with confirmed_flush_lsn:

confirmed_flush_lsn: The address (LSN) up to which the logical slot’s consumer has confirmed receiving data. Data corresponding to the transactions committed before this LSN is not available anymore. NULL for physical slots.

So this is the latest LSN acknowledged by the slot’s consumer.

In general, streaming will be continued from the next entry in the write-ahead log (WAL) after this LSN when restarting a consumer

(we’ll get to one exception later on).

Let’s confirm this by creating a slot using the test_decoding plug-in:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

-- Creating a table for experimenting

CREATE TABLE inventory.customers (

id SERIAL NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

first_name VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

last_name VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

email VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL UNIQUE,

is_test_account BOOLEAN NOT NULL

);

ALTER SEQUENCE inventory.customers_id_seq RESTART WITH 1001;

ALTER TABLE inventory.customers REPLICA IDENTITY FULL;

-- Creating a replication slot

SELECT

*

FROM

pg_create_logical_replication_slot('demo_slot', 'test_decoding');

|

The |

Insert some data:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

INSERT INTO

inventory.customers (first_name, last_name, email, is_test_account)

SELECT

md5(random()::text),

md5(random()::text),

md5(random()::text),

false

FROM

generate_series(1, 3) g;

And consume it using Postgres' built-in SQL interface for working with logical replication streams (output shortened for readability):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

SELECT * FROM pg_logical_slot_get_changes('demo_slot', NULL, NULL);

+-----------+-----+-----------------------------------------------+

| lsn | xid | data |

|-----------+-----+-----------------------------------------------|

| 0/1DDC648 | 765 | BEGIN 765 |

| 0/1DDC6B0 | 765 | table customers: INSERT: id[integer]:1138 ... |

| 0/1DDF4D0 | 765 | table customers: INSERT: id[integer]:1139 ... |

| 0/1DDF610 | 765 | table customers: INSERT: id[integer]:1140 ... |

| 0/1DDF780 | 765 | COMMIT 765 |

+-----------+-----+-----------------------------------------------+

SELECT 5

The slot’s confirmed_flush_lsn is the last consumed LSN, 0/1DDF780, automatically acknowledged by pg_logical_slot_get_changes():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

SELECT

slot_name, plugin, restart_lsn, confirmed_flush_lsn

FROM

pg_replication_slots;

+----------------+---------------+-------------+---------------------+

| slot_name | plugin | restart_lsn | confirmed_flush_lsn |

|----------------+---------------+-------------+---------------------|

| demo_slot | test_decoding | 0/1DDC610 | 0/1DDF780 |

+----------------+---------------+-------------+---------------------+

If we were to do more data changes and consume the slot again, we’d receive any events after LSN 0/1DDF780.

restart_lsn: Handling Concurrent Transactions

So far, so good; what’s the deal with restart_lsn then?

Unfortunately, the official docs are a bit vague on this one:

restart_lsn: The address (LSN) of oldest WAL which still might be required by the consumer of this slot and thus won’t be automatically removed during checkpoints unless this LSN gets behind more than max_slot_wal_keep_size from the current LSN. NULL if the LSN of this slot has never been reserved.

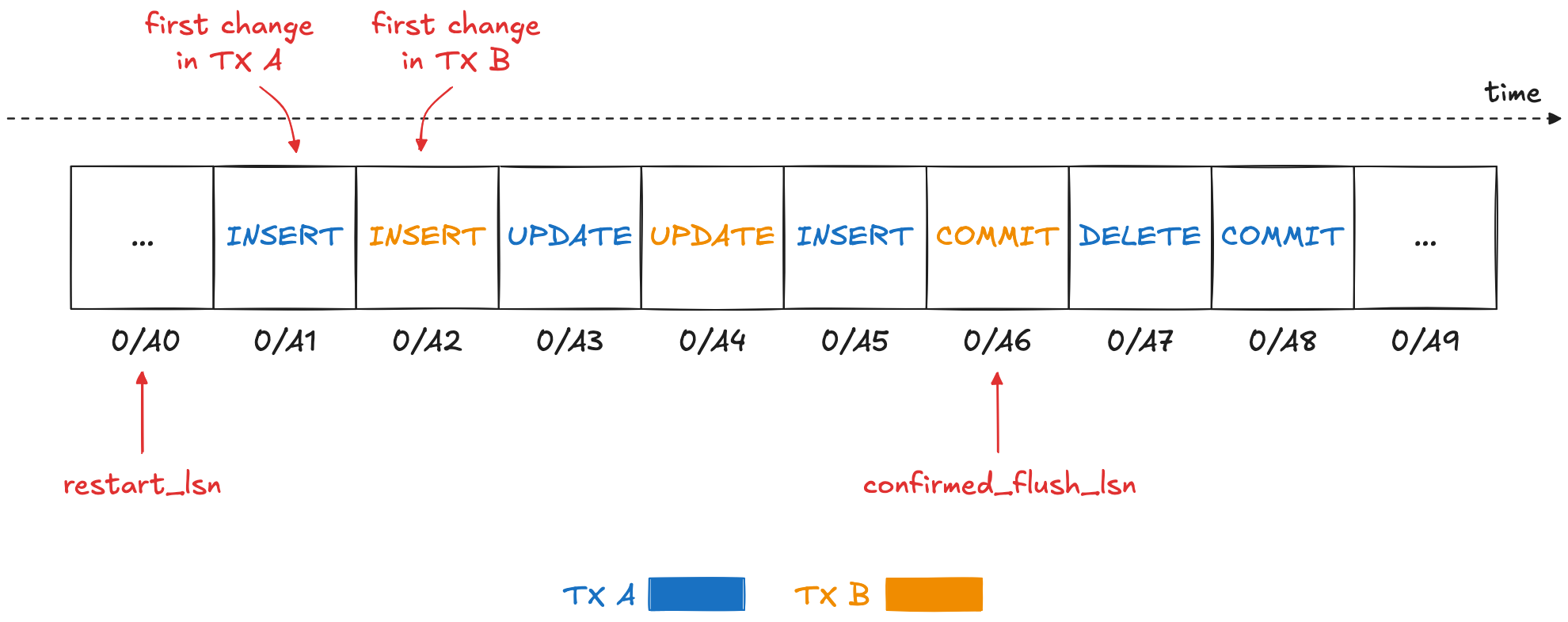

When would a consumer need access to events older than its last confirmed LSN? This becomes clear when we examine how the WAL captures multiple transactions running concurrently, and how these are streamed to logical replication consumers. By default, the events of a transaction will only be published after the transaction has been committed. Suppose there are two transactions A and B running at the same time, with transaction A beginning before transaction B, but B committing before A. The WAL might look like this (LSNs shortened for readability):

When transaction B commits, all its changes get published to the consumer of the replication slot,

which eventually will confirm the latest LSN it has seen, 0/A6 (the LSN of the commit event).

This does not mean though that the database can prune all earlier WAL sections just yet.

At this point, transaction A still is running, so any WAL sections with the changes from this transaction still need to be retained until the transaction commits and the change events have been received and acknowledged by the replication slot consumer.

And this is exactly the purpose of the replication slot’s restart_lsn:

it is the latest LSN prior to all transactions which either are still in-flight, or which have committed but not been acknowledged by the consumer yet,

in the example 0/A0.

It acts as a retention boundary—WAL segments before this point can be safely discarded.

This way of handling concurrent transactions has a few important implications:

-

Consumers of logical replication cannot rely on the LSNs of received events to be strictly increasing. As transactions are exposed in commit order, events with a lower LSN can be published after events with a higher LSN. Only the tuple

(commit_lsn, lsn)is guaranteed to be strictly increasing, i.e. commit LSNs are non-decreasing, and the LSNs of the events within one and the same transaction are non-decreasing. -

Large or long-running transactions prevent the database from increasing the restart LSN of replication slots and hence may cause excessive amounts of WAL to be retained; therefore, you should generally avoid these types of transactions when possible

You also might wonder how the logical replication engine identifies the events to publish when encountering a COMMIT event in the WAL.

A data structure called the "reorder buffer" is used for this purpose.

It stores all events retrieved from the WAL, keyed by transaction id.

Upon processing a transaction’s commit event,

all events for the transaction are fetched from the buffer and emitted to the consumer.

That way, no costly seeking in the WAL is required.

The buffer can spill over to disk for large transactions when reaching a given threshold,

defaulting to 64 MB and configurable via the logical_decoding_work_mem setting.

As this means additional disk I/O though,

you should keep an eye on the amount of disk spill, using the pg_stat_replication_slots view.

Mid-Transaction Recovery

Above, I mentioned there’d be one situation where a consumer may receive events from before the confirmed_flush_lsn of its replication slot when resuming to process a replication stream after a downtime.

This happens when confirmed_flush_lsn points to an event in the middle of a transaction, rather than to a COMMIT event.

In this case, all events of the entire transaction will be replayed to the consumer, starting with a BEGIN event.

Let’s try to reproduce this situation.

pg_logical_slot_get_changes() always returns all the events of a transaction, also when instructed to fetch a lower number of events.

So we’ll have to be a bit more creative.

First, let’s retrieve the current LSN and then insert a couple of rows into the customers table in a transaction:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

SELECT pg_current_wal_lsn();

+--------------------+

| pg_current_wal_lsn |

|--------------------|

| 2/50955BD8 |

+--------------------+

BEGIN;

INSERT INTO

inventory.customers (first_name, last_name, email, is_test_account)

SELECT

md5(random()::text),

md5(random()::text),

md5(random()::text),

false

FROM

generate_series(1, 3) g;

COMMIT;

To find out the LSN of one of the individual row inserts, we can use the pg_walinspect extension;

it provides the pg_get_wal_records_info() function which lets you take a view at the WAL events of a given LSN range

(as an aside, this shows that there is no explicit event for the begin of a transaction in the WAL;

the BEGIN events in a replication stream are inserted by the logical replication system):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

SELECT

start_lsn, end_lsn, xid, record_type

FROM

pg_get_wal_records_info(

'2/50955BD8',

pg_current_wal_lsn()

);

+------------+------------+-----+---------------+

| start_lsn | end_lsn | xid | record_type |

|------------+------------+-----+---------------|

| 2/50955BD8 | 2/50955C40 | 777 | LOG |

| 2/50955C40 | 2/50956E18 | 777 | INSERT |

| 2/50956E18 | 2/50956E90 | 777 | INSERT_LEAF |

| 2/50956E90 | 2/50956F90 | 777 | INSERT_LEAF |

| 2/50956F90 | 2/50957030 | 777 | INSERT |

| 2/50957030 | 2/50957070 | 777 | INSERT_LEAF |

| 2/50957070 | 2/50957170 | 777 | INSERT_LEAF |

| 2/50957170 | 2/50957210 | 777 | INSERT |

| 2/50957210 | 2/50957250 | 777 | INSERT_LEAF |

| 2/50957250 | 2/50957350 | 777 | INSERT_LEAF |

| 2/50957350 | 2/50957388 | 0 | RUNNING_XACTS |

| 2/50957388 | 2/509573B8 | 777 | COMMIT |

+------------+------------+-----+---------------+

Next, move the replication slot forward to the LSN of the second INSERT:

1

SELECT pg_replication_slot_advance('demo_slot', '2/50956F90');

If you now retrieve the changes from the slot, you’ll see that it still returns all the events from that transaction,

including the first INSERT, despite this one having an LSN older than confirmed_flush_lsn:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

SELECT * FROM pg_logical_slot_get_changes('demo_slot', NULL, NULL);

+------------+-----+---------------------------------------------------+

| lsn | xid | data |

|------------+-----+---------------------------------------------------|

| 2/50955BD8 | 777 | BEGIN 777 |

| 2/50955C40 | 777 | table customers: INSERT: id[integer]:10001159 ... |

| 2/50956F90 | 777 | table customers: INSERT: id[integer]:10001160 ... |

| 2/50957170 | 777 | table customers: INSERT: id[integer]:10001161 ... |

| 2/509573B8 | 777 | COMMIT 777 |

+------------+-----+---------------------------------------------------+

It is therefore generally advisable to confirm commit LSNs,

as it allows the database to discard all the WAL elements for that transaction.

When using Debezium, you can set the connector option provide.transaction.metadata to true in order to achieve that.

Otherwise, Debezium would only acknowledge the LSN of the last event within a transaction.

This is due to the constraints of the Kafka Connect framework, which only triggers a commit of source offsets when emitting records to Kafka.

Looking Forward: Streaming In-Progress Transactions

One last thing worth mentioning is that since version 14, Postgres also supports logical replication of in-progress transactions. This can be an interesting option to mitigate the issue of replication slots retaining a lot of WAL for large transactions, and it also can help to reduce end-to-end latencies as CDC tools can process change events (format them, filter them, etc.) before a transaction commits.

On the other hand, it also shifts quite a bit of complexity into the CDC layer, which now—similar to Postgres' internal reorder buffer—requires a way to store all the events of a transaction, so as to drop the events of transactions which eventually get rolled back. Debezium tracks this feature under the issue DBZ-9309.